In part 1 of this series, I laid a foundation to discuss the factors that are driving companies to put more of their IT spend at the discretion of their CMOs. As a result, there are growing signs that the challenges of IT organizations are becoming marketing’s as well. Let’s explore some of these.

1. Business Goals vs. Internal Goals

In almost all organizations, IT is a support function. While key in allowing the company to run its operations and serve customers, it is mainly considered a business enabler. The language spoken by the business units on the front lines versus that spoken by IT is quite different. As such, deriving IT goals from the corporate strategy and plan is not straightforward. IT management needs to invest a lot of time and effort into understanding how to best serve the business and in making the decisions that will help support those insights.

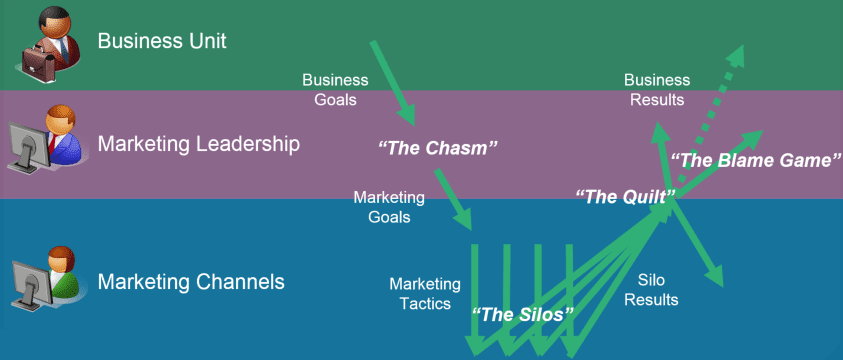

Similarly, in many cases on the marketing side, business KPIs set by corporate strategy do not exactly conform to marketing goals. Though the languages spoken by the various business units and by marketing are undoubtedly closer than those that dominate the halls of IT, there is still a gap. While the business may be targeting a certain level of profit in China, a team within marketing may have a goal of driving a certain amount of users to the Chinese website. While the latter will hopefully drive the former, they are not really one and the same. Like IT, it is up to the marketing executive to “translate” the business goals into a plan and that takes time and effort.

2. Structural Challenges

Since IT is often siloed – teams tend to be structured around a specific system – each part of the organization has an even harder time understanding how its goals are serving the greater good. The result is “tunnel vision,” with each team focusing only on delivering on its own plan, despite the inter-dependency that obviously exists between the teams.

Much like IT, marketing often has a siloed structure. Typically, it revolves around the media channels, with each channel covered by a different team and headed by a leader, whose goals are to deliver on their portion of the marketing plan.

Each channel manager cares first and foremost about meeting her own goals, as opposed to the greater marketing plan (and through it, hopefully, the business plan). In bidding terms, one might think of it as analogous to keyword optimization vs. portfolio optimization: the former will have each keyword caring only about reaching its own goal, whereas the latter will have certain keywords “taking a personal hit” for the greater good, which is optimizing the entire portfolio’s results.

3. Fragmentation

As the CIO needs to understand how well IT is serving the business (read: justifying its existence), data from many different systems needs to be pulled together and presented in a usable way to drive decision-making. Getting to this consolidated view is not an easy feat, even for an organization of technologists.

What further complicates matters is the fact that completing a business process means a transaction has to go through a chain with many different links: network, databases, application servers, web servers, the user’s machine, and back again. This chain is only as strong as its weakest link – break one and the business process cannot be completed. In case something goes awry, it’s likely to find teams pointing a blaming finger at someone else – anyone else, really – to prove they are not at fault. This renders getting to the bottom of a severe IT issue quite complicated, and will usually require an “all hands on deck” emergency mode.

The above is analogous to what happens in marketing. As the budget cycle advances, the marketing executive wants to monitor progress. Each channel manages its investments through a different system, requiring every disparate system’s data to be brought together into a “single source of truth” – be it a report, dashboard, presentation, or something else – that can serve as the mirror, or scorecard, in front of marketing’s eyes. Such an effort takes considerable time and resources whenever a periodic review approaches, and puts the entire organization into preparation frenzy.

This periodic marketing performance review can take two shapes, depending on the results presented. If everything is working according to plan, almost no questions are asked. After all, if it isn’t broken, why fix it, right? The dynamic will be much different, however, if execution is falling short. In that case, the marketing exec will put his or her inquisitor cap on, and everyone else may be guilty until proven innocent. Because of the siloed org structure, teams may be pointing the finger at someone else, and getting to the bottom of what actually went wrong – and, more importantly, how to fix it – can be quite painful.

Of course, some marketing challenges cannot be drawn as equivalent to those of IT. One stems from the fact that, unlike IT, marketing communicates with the customer directly. If each silo is left to manage its customer communication without noticing what other channels are saying (and how), this causes a dissonance: instead of one voice representing the company and building what would hopefully be a long-term relationship with customers, multiple voices emerge, cause confusion, and hinder the message.

What marketing and IT teams can learn from one another is that they have more in common than one would think. In part 3, I’ll explore what this means for the future of the marketing organization.